The Long March

THE EVACUATION OF STALAG LUFT III

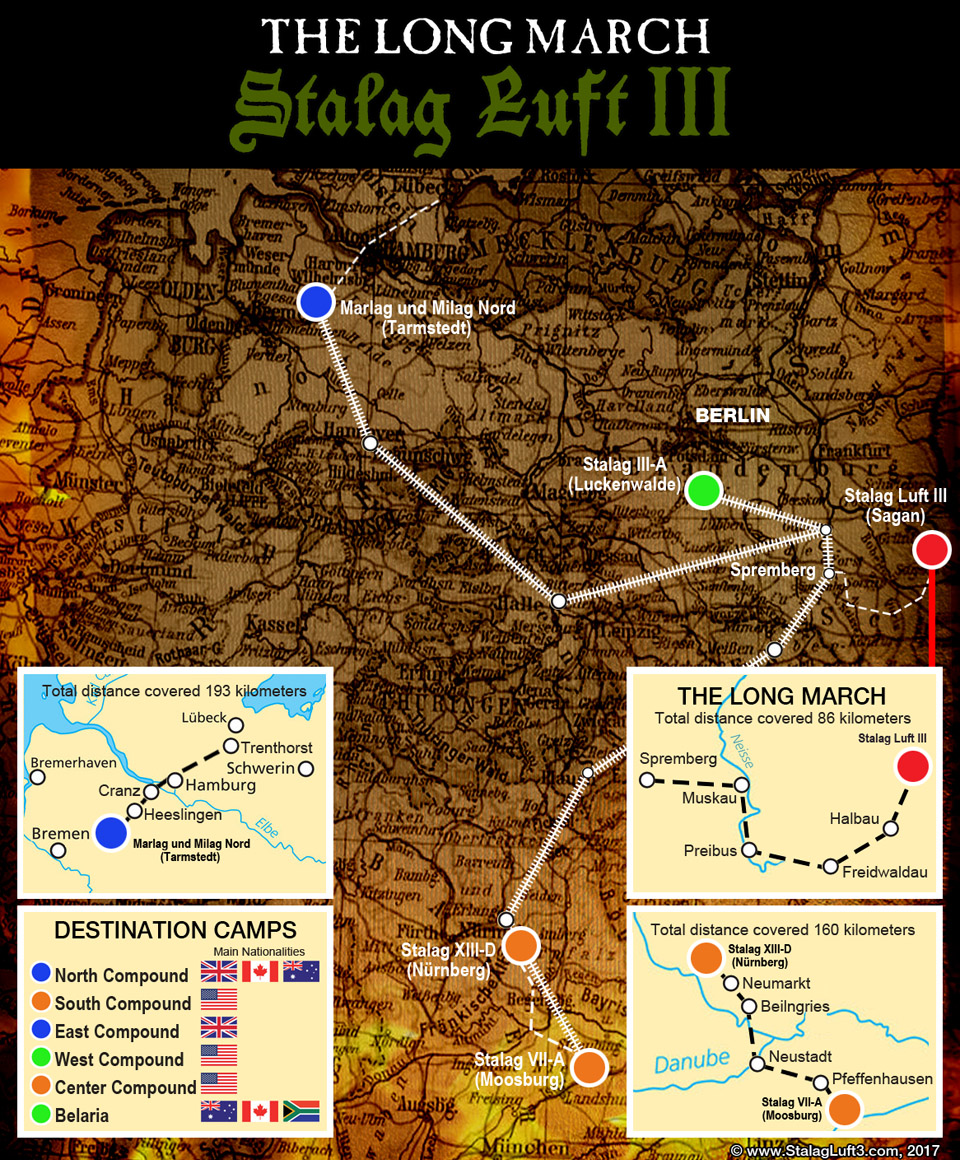

As the end of January 1945 drew near, Russian forces under the command of Marshal Konev had advanced to within less than 20 kilometers of Stalag Luft III. The POWs could hear the constant battle and knew that liberation was only a matter of days away. However, on the evening of 27 January, a call came through to Kommandant von Lindeiner from Berlin. Adolf Hitler had ordered the immediate evacuation of the camp. The POWs in all six compounds were instructed to prepare to march that very night. The men hurriedly collected whatever they could in their packs. Clothes and food rations were the priority, with most personal possessions abandoned. Some of the POWs, such as F/Lt Keen in North Compound, actually managed to find the time to cobble together a makeshift sled.

The American airmen in the South Compound were the first to leave at 9.20 p.m. The North and East Compounds followed between 1 a.m. and 3.15 a.m. on the following morning, joined shortly after by the Center Compound. The prisoners from Belaria did not depart until 6 a.m. on the morning of 29 January. Each man was given a Red Cross food parcel when they passed through the vorlager. In all, over 10,000 men marched through the gates of Stalag Luft III that night and that of the following. The conditions that confronted them were extreme, with sub-zero temperatures and a thick covering of snow. Indeed, it was one of the coldest German winters in living memory. In a column that stretched for almost 5 kilometers, the men marched hour after hour, relieved only by 10-minute halts.

The POWs were not the only ones heading away from the Russian advance. So too were the German people of those eastern regions, who knew full well that the Red Army was not about to forget the atrocities committed in their homeland by the Führer’s hand. Families with their entire world packed on a cart struggled alongside those with no world left to carry. Some of the POWs familiar with military history compared the scale of what they were witnessing to Napoleon’s epic retreat from Moscow.

F/Lt Keen and the others from North Compound reached the town of Halbau (Iłowa) at 9.15 a.m. that day. Instead of resting there as they had hoped, they were informed that they had a further 11 kilometers to march to the next town before they could take a proper break. At noon they entered Freidwaldau (Jeseník), but as no adequate shelter could be found, the men were forced to trek onward another 6 kilometers to the village of Leippe (Lipowa) where they were finally allowed to rest in barns. They had marched 34 kilometers.

After some poor sleep and little food, the men were back marching again at 8.00 a.m. the next day. At around noon, they reached the town of Priebus (Przewóz), and the men were given 30 minutes to muster some food, either from their pack or by trade with the locals. The weather conditions were still severe, and by this time many men had already fallen by the way.

- Sagan

- Freidwaldau

- Von Arnim Estate - Musksau

- Spremberg

By the evening of that day, the men had progressed to the old Medieval spa town of Muskau (Bad Muskau) on the Neisse river. Following complaints from the Senior British Officer, billeting in Muskau was somewhat better organized, with the men housed in a variety of locations, including a cinema, glass factory, brickworks, pottery, local French POW camp, and the riding school of a German nobleman, Count von Arnim.

On 31 January, the US POWs from South Compound who had lead the march, as well as some occupants of the West, arrived at the rail hub of Spremberg. They were loaded into a string of cattle-trucks. Conditions inside were bleak, filthy and severely overcrowded. Two destinations awaited the men, both in deepest Bavaria, either Stalag XIII-D at Nürnberg or Stalag VII-A at Moosburg. In the days that followed many POWs from the other compounds would, either correctly or through confusion, find themselves channeled to one or the other of these camps.

Back in Muskau, on the afternoon of 1 February, orders were given that the men of North Compound, as well as another 500 from the East Compound, should ready themselves to continue marching that night. Their destination was also Spremberg. During the three days camped in Muskau, the weather had improved, and a thaw had set in, though this brought with it a new set of challenges. With the sleds less helpful, some of the men hurriedly attempted to barter with the locals for some form of wheeled conveyance, such as a pram or wheelbarrow to carry their loads.

POW Watercolor of The Long March from Stalag Luft III

At 10.45 p.m.the men from North Compound and the compliment from the East set out to march through the night. They had to leave behind another fifty-seven of their number who were too sick to continue. This leg of the journey was the quietest, with only the grate of a few remaining sleds on the road disturbing the night. It was also the most difficult as the already exhausted men faced more demanding terrain.

Along the way, locals on the whole had reacted with compassion to the plight of the POWs, offering water and hot drinks, though this was frequently denied by the German guards. One woman, bearing coffee, explained that her husband was a POW in England and therefore she felt an empathy with the men. The guards, however, shared no such kindly sentiments.

As dawn broke the next day, the column paused to rest a few hours in the village of Graustein (Spremberg suburb). Spremberg was only 7 kilometers away, though what lay beyond there for the men was still a mystery.

At 2 p.m. the POWs from the North and East Compounds finally reached Spremberg where they were quartered in the reserve barracks of the 8th Panzer Division. For the first time in days, the men had hot food and access to warm water. It was only at this juncture that they discovered their final destination, the maritime POW camp Marlag und Milag Nord which lay nearly 500 kilometers away at the opposite side of the country. The respite, however, was brief as by 4.30 p.m. the men were marched down to the town’s rail depot and crammed like the previous compounds into a row of cattle trucks. Sustenance for this next stage came in the shape of more Red Cross food parcels, which had been hauled by wagons from Stalag Luft III. Amid clouds of steam and the clatter of wheels, the train began its perilous journey through the heart of war-torn Germany bound for the town of Tarmstedt, home to Marlag und Milag Nord.

The following day, the POWs from West Compound, along with those from Belaria, arrived at the Panzer barracks in Spremberg. There they were also loaded onto trains, though their journey proved to be a little shorter. Their destination was Stalag III-A at Luckenwalde, about 50 miles south of Berlin. Departing that evening, they arrived in Luckenwalde in the late afternoon of the next day. After a short march from the railway station to the camp, they were searched then settled into their new accommodation.

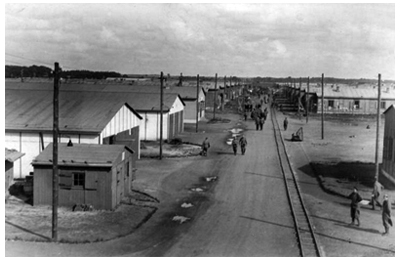

The train carrying the remaining 1,916 men from the North and East Compounds arrived at Tarmstedt Station at 5 p.m. on 4 February. It was not a particularly encouraging scene that greeted them, the sky was dark, and the rain was pouring. The rail journey had been just one more chapter in a grim tale, with a shortage of water and an absence of toileting facilities. Amid all this, the famed Klim milk tins had found yet another use. F/Lt Keen perhaps summed up the whole experience best in his Wartime Log, “Hell of a journey.” The men trudged the last 3 kilometers to the camp which was in the nearby village of Westertimke. By this time events had taken their toll. Many of the men were literally on their last legs, suffering from frostbite, dysentery, and sickness. To make matters worse, it took nearly 7 hours for the German authorities to process each member of the column and admit them through the gates. It was now 5 February.

Marlag und Milag Nord (Tarmstedt)

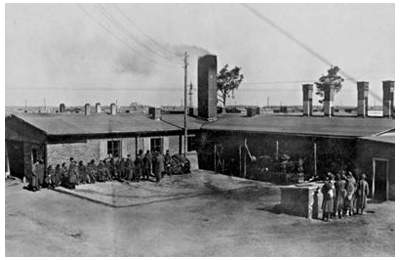

Stalag III-A (Luckenwalde)

By daybreak of 22 April, the Red Army had swept through eastern Germany and reached the gates of Stalag III-A. The guards had already fled and the POWs, including those from Stalag Luft III, welcomed their Russian liberators. With the camp now under the supervision of Captain Medvidw, a convoy of fifty trucks soon arrived laden with food, clothes and medical supplies. For the men in Stalag III-A, the liberation process was a little slower than in the other camps in question owing to the diplomatic protocols involved with it now being in Russian territory and control. As time dragged on, some of the men resorted to hitch-hiking to expedite their repatriation.

MARLAG UND MILAG NORD (Tarmstedt)

The men from the North and East Compounds of Stalag Luft III were given little time to settle into their new location. On 9 April, with the advancing Allied forces only a few miles away in Bremen, the Kommandant issued orders that 3,000 of the POWs, including the men from Stalag Luft III, should ready themselves to march the following day. Once again, F/Lt Keen and his fellow POWs from Stalag Luft III were about to see freedom snatched away from them. Under a blanket of fog, the column left the camp early the next morning, with RAF POWs at the head and senior officers and German supply wagons occupying the rear. The column passed through the town of Zeven in the evening of that day, resting briefly before continuing to Heeslingen where they camped out for the rest of the night in the surrounding fields. The men were allowed to trade with the local villagers for extra rations of food.

At around 10 a.m. the next day, a tragedy would occur that would define the march. Although the weather was clear and the column displayed its POW status with Red Cross insignia, it suddenly came under attack by RAF fighters, resulting in a number of the men being wounded and killed. F/Lt Keen scrambled for cover in a shallow ditch as the bullets strafed the ground he had just been walking. After having faced the might of the German Luftwaffe on endless sorties, the irony that a bullet from his own side had almost achieved what they had failed to was not lost on him. Over the coming hours the column, was subjected to several more friendly fire attacks. In the light of the rising casualties, an agreement was struck between the POWs and their German captors that they would only march by night. During the previous events, a group of American POWs had seized the moment and escaped. Leading the breakaway bunch was Col. Peter Ortiz, who after the war would go on to work as an actor with the legendary director John Ford.

By 15 April, the column had reached the banks of the River Elbe at Cranz near Hamburg where they stayed overnight before crossing the next morning by two old ferries, The Franz Schubert and The Mozart. Day after day, the men marched onward, foraging for food and sleeping wherever they could find, still having no real idea where they were bound. Finally, on 23 April, after a grueling trek of over 193 kilometers, F/Lt Keen and the other men from Stalag Luft III neared the Baltic port of Lübeck where their progress was put on hold by a Typhus scare in the city. They spent five days in the village of Hamberge, then moved to Trenthorst, a small settlement on the estate of German business magnate Philipp F. Reemtsma, of cigar fame. However, no more marching was required of them as on 1 May 1945 the village was liberated by Allied forces.

And so had come to an end The Long March for the men of North Compound, Stalag Luft III.

- Zeven

- Elbe Ferry Franz Schubert

- Hamberge

- Reemtsma Estate, Trenthorst

A CINEMATIC FOOTNOTE

Marlag und Milag Nord was later used as one of the principal locations for the British movie, The Captive Heart (1946).

Col. Peter Ortiz (w/ patch) with John Wayne in John Ford's classic Rio Grande (1950)

STALAG XIII-D (Nürnberg) and STALAG VII-A (Moosburg)

With the US forces closing in on Stalag XIII-D, the POWs, those from Stalag Luft III included, were marched another 160 kilometers south to Stalag VII-A (Moosburg), not far from Munich. The bulk of the men reached Moosburg on 20 April, though some had dropped out along the way, unchallenged by the German guards who were demoralized by the specter of their country’s imminent defeat. Originally constructed to hold 14,000 POWs, the influx of two waves of men from Stalag Luft III, plus the results of a growing exodus from other evacuated camps, had inflated the population of Stalag VII-A to an overwhelming 130,000. Living conditions were therefore basic at best, and many of the men opted to sleep in tents or just outdoors. However difficult life was in the camp, most of the US airmen from Stalag Luft III were at least once again reunited.

On the morning of April 29, with elements of the 14th Armored Division of Patton’s 3rd Army approaching Stalag VIIA, a fierce firefight besieged the compound for a while. There was some confusion over the source of the action. Some witnesses attributed it to the initial skirmishes between the US forces and troops within the camp. Others, however, offered a more sinister version of events. They claimed that the Gestapo had attempted to seize control of the camp from the Wehrmacht. In a final act of vengeance against Allied airmen, according to the story, Hitler had issued an order to kill all of the prisoners in the camp. The Gestapo, assisted by SS troops, had endeavored to complete that dictum. However, the German army had stepped in to prevent the slaughter. Whatever the explanation for the gunplay, at 12.15 p.m. the Stars and Stripes replaced the German Hakenkreuz (swastika) over Moosburg. Soon after, the American forces arrived, and the first tank defiantly breached the barbed wire of the compound. The men from Stalag Luft III, like everyone else held in the camp, erupted in celebration, mobbing the tank and the others that followed.

General George S. Patton

Two days later, and with all the expected fanfare, General George S. Patton rolled into the camp in his signature jeep and with his equally famous ivory gripped pistols slung on each hip. As the American airmen from Stalag Luft III beheld the euphoric scenes, they knew at long last they were free.

As Germany imploded on all sides in the face of impending military defeat, the POWs from Stalag Luft III were evacuated to camps elsewhere in a series of epic Long Marches

PERSONAL ACCOUNT FROM THE WARTIME LOG OF F/LT RAYMOND KEEN

27-1-45 At 9pm we were told to be ready to march at an hour’s notice, blizzard raging outside, hastily began to make a wooden sledge and fill a hastily made pack.

28-1-45 At 3am we pulled out of the main gate, an amazing scene, bitterly cold weather. Continuous heavy snow, lines of POWs stretching for miles. As the night wore on men began to fall back to the rear of the column in bad condition. Passed through Halbau at 9-15am and arrived at Freidwaldau at 12.15am. Marched another 6 kilometers to a barn outside a town. In bitter weather and blowing blizzard 700 of us were pushed in a barn, bare of straw, some of the men in very bad condition. Bitterly cold – Had marched 34 kilometers.

29.1.45 Set off again at 8.30am still blowing a blizzard, bitterly cold, passed through Preibus at 11.45am. Many falling back, some very exhausted, arrived at Muskau at 7.00pm, had continued a blizzard all day. Most of the men exhausted. Spent three days in a brick factory and part of the last day at Count Von Arnim’s riding stable. Covered another 24 kilometers.

1-2-45 Left Muskau at 10pm, thaw had set in and roads in bad state. Had to leave sledge and carry pack on back. Marched 19 kilometers, worst march of the journey, and arrived at a barn in a small village, feeling very exhausted. Feet in quite good condition, large number of sick men. Arrived at 6am and left at 11am.

2-2-45 Left for Spremberg at 11.30am and covered 9 kilometers, arriving there at Adolf Hitler Regiment Panzer Barracks at 2pm. At 5.pm marched 2 kilometers to a railways siding, 50 cattle trucks there.

3-2-45 In cattle trucks all day, passed through Halle at 7pm, suffering caused through lack of water.

4-2-45 Passed through Hanover at 8.30 and arrived at Tarmstedt – OST at 4.30.pm. Hell of a journey. Marched 3 kilometers to the new camp in pouring rain. Stood outside gate for four hour and then searched. Thirteen of us placed in an empty room with wet straw to sleep on. Feeling pretty done in but glad to fall down and sleep anywhere. Had marched 90 kilometers and done 300 in the cattle truck. Majority sick, some in very bad state.

LIBERTY

Kept awake during the night May 1st, 1945, we were quartered around barns 13 kilometers from Lubeck. Fighting had been drawing closer in the last few days, on the morning of the 2nd May we could hear a heavy battle raging both sides of us on the autobans. Could hear tanks and machine guns clearly. At 10am a party of SS Troops passed through our village looking very tired. The road north to Kiel swarming with Germans trying to get North, they were in such a hurry that not one of them fired at us. We were getting very excited, as we realized that release was near. At 2pm a British armoured car of the Cheshire regiment swept into the village, and told us that we were free. Great scenes of rejoicing. Disarmed the guards and took over the village. Fed the starved foreign workers. Germans who had ill treated us were taken for a stroll.

Gradually moved back to West Germany by lorries, to Rheiner airport where on May 9th we were flown back to England, had great welcome. Hot showers and SPRING BEDS.

Spent 763 days in captivity.